In the past I’ve tried my best to describe the history that underpins current issues within the Middle East, while at other times I’ve attempted to summarize the ethnic and sectarian politics in specific countries like Syria. Now, I would like to focus more specifically on the intersection of political ideology, sectarianism, and the new regional rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia that has dominated coverage of the region. My goal is to illuminate the apparently intractable sectarian conflict in the region and help to contextualize the recent conflict in the Middle East.

The rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran was brought into sharp relief when the Saudi Royal family executed Nimr Baqr al-Nimr, a prominent Shi’a activist and critic of the the Saudi monarchy, which precipitated an angry crowd sacking the Saudi embassy in Tehran. Much has been made over the interminable origin of this recent spat between predominantly Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shi’a Iran. It’s tempting to see the conflict between these two nations as part of an ancient rivalry between divisions in Islam, but as I’ve written in the past, the origins of this conflict are actually quite recent, and are the product of changing political ideologies and regional politics rather than religion itself.

The Middle East has undergone a series of transformations over the past century that have helped shape the current conflict today. Notably, many of the current boundaries of the region are the product of an agreement between great powers at the conclusion of WWI. The Sykes-Picot Agreement helped establish many of the Arab states today: Syria and Lebanon were partitioned by the French mandate, partially with the goal of creating a majority-Christian homeland in Lebanon. Israel/Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq were all administered by the British, who had their own designs on the territories they controlled. While some boundaries were drawn with religion in mind, most were the result of negotiations with France and the newly independent Turkey or even the odd hiccup. Beyond the geography witnessing upheaval, the political ideology of the region has witnessed remarkable change in the past century as well.

(Source)

These mandates did not remain under European patronage for long; by 1954 countries in the region sought legitimacy not from outside powers but from within. While religion remained important in social life, it did not form the ideological foundation of these new states. Countries were divided between hereditary monarchies and republics who derived legitimacy their from various revolutionary ideologies, often based on ethnic nationalism. During this time both Iran and Saudi Arabia were monarchies and were aligned with the West, which limited their competition with each other.

Instead, the Saudis were coping with the rise of Arab nationalism and its revolutionary proponents. Charismatic leaders like Gamal abdul-Nasser captivated mainstream Arab thought with a mixture of socialist economics and a pledge to unite the disparate Arab states against Israel. By 1967 the Saudi kingdom had seen Egyptian, Syrian, Iraqi, North Yemeni, and Libyan monarchies all fall to republican revolutions. Saudi Arabia resisted the spread of Arab Republican movements both politically and militarily, sending troops into North Yemen to support the monarchy there; this was the beginning of the little known Arab Cold War, where monarchies and Arab Republics competed for regional influence. But Nasser’s rise would be cut short, and with it his associated political vision.

When Nasser demanded that UN peacekeepers withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula in June of 1967, it precipitated a major confrontation between the Arab world and Israel, which proved disastrous for both the Egyptian state and for the secular ideology that underpinned it. In less than one week the armies of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and (to a lesser extent) Iraq were defeated by Israel. Egypt’s entire air force was wiped out in a matter of days and more than 10,000 Egyptian troops lost their lives. In addition to the crippling military defeat, Israel was now in control of the remaining 22% of Palestine, including Jerusalem. The loss marked the beginning of the end of Arab nationalism’s eminence in political thought. While all of this was happening in the Arab world, Iran was facing its own political transformation.

Just as the Arab states were subject to Western influence at the end of the First World War, Iran too was the victim of power politics. For over a century Iran was the front line in the so-called Great Game, a geopolitical rivalry between the British and Russian empires. The Bolshevik revolution dramatically altered this rivalry and turned Iran in a major faultline in the Cold War. The British and US saw Iran as a front-line that separated the Soviet Union from the Middle East, and as such they went to great lengths to prop up its monarchy, led by Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Though it was a monarchy, Iran’s political system was more open than Saudi Arabia’s and the legislature (Majles) was able to appoint a prime minister with some executive powers. In 1951 the Majles appointed Mohammad Mossadegh as Prime Minister, who instituted a variety of progressive reforms including nationalizing the then British-controlled oil industry. This angered the British and precipitated a CIA and MI6 led-overthrow of the government, with the acquiescence of the Shah. To reward the monarchy for its support in the coup and favorable energy policies, the US bankrolled the regime and helped establish the SAVAK, a brutal secret police force and security service that acted to silence opponents of the monarchy.

This betrayal of democratic values led to a growing disdain for the regime and its Western allies, which would eventually boil over in the revolution of 1979. Not all of the activists in this revolution were Islamists, but the leadership of Ruhollah Khomeini proved irresistible to the other political factions. By 1982 the Islamists aligned with the Supreme leader had crushed the internal opposition and consolidated power. The ideological basis for this revolution was overtly religious, based largely on Khomeini’s concept of Velayat-e faqih (Guardians of the Jurist). The State would be led by a jurist or Supreme Leader, a pious religious figure who would preside over a complex arrangement of elected and unelected leaders. While the basis of this revolutionary state was centered on Shi’a Islam, its consequences have altered both the geopolitical and the ideological landscape of the entire region.

The new regime began to export its revolution almost immediately, using the newly-formed Revolutionary Guards, the armed wing of the revolution to support movements modeled after their own. This included sending forces to southern Lebanon (where they essentially created Hezbollah and empowered the beleaguered Shi’a community), funding and supporting Shi’a insurgents in Iraq during Saddam’s rule, and inspiring and allegedly supporting insurgents in Saudi Arabia’s predominantly Shi’a Eastern Province. The revolution also marked the beginning of several events which upset the sectarian balance of power in the region.

(Source: Dr. Izady, Gulf/2000)

(Source: Dr. Izady, Gulf/2000)

Shortly after rising to power in Iran, the Islamist regime was invaded by Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, thus beginning an eight year conflict which would claim hundreds of thousands of lives and create immeasurable suffering. This war posed a challenge for Saudi Arabia, as it had frosty relations with Saddam’s Ba’athist republic but even worse relations with the revolutionaries in Tehran; it sided with Iraq and heavily funded its military campaign. Syria was one of the only regional actors to support Iran in this conflict, which produced a lasting connection between the two regimes. As the war drug on, Iraq became increasingly dependent on support from its Sunni neighbors, which did not go unnoticed in Tehran. Eventually the war ended in a stalemate and Iraq was so devastated by it that Saddam sought recourse by invading Kuwait. This led to both Iran and Iraq becoming isolated in the 1990s in the region and also by the US under the policy of dual containment.

The end of the Iran-Iraq war (1988) and the settlement that ended Lebanon’s civil war (1989) helped to de-escalate the rivalry between Sunni states and Iran in the 1990s, though tensions remained high. Iran continued its support for Hezbollah in Lebanon, while Saudi Arabia and the its Gulf allies supported the Sunni community there, which was given a stronger political role after the civil war ended. Sunni Arabs continued to dominate government and military posts in Saddam’s regime, but the country was isolated by its neighbors over its invasion of Kuwait. This period of calm and equilibrium was upset by two key events which brought the regional politics of sectarianism into sharp relief.

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, it may have gotten rid of a republican regime that was disliked by Saudis, but it also dramatically altered Iran’s position in the region. Iraq’s Arab Shi’a majority had long been ruled by a regime that favored Sunni Arabs, but the invasion reversed this and empowered leaders of the Shi’a community who had long connections with Iran. Saudi Arabia has expressed disapproval with Baghdad’s sectarian policies and its close relationship with Iran, and relations between the two states remain strained.

Shortly after the invasion of Iraq, Lebanon’s delicate political arrangement was also thrown into disarray; on February 14, 2005 Rafik Hariri, the Sunni Prime Minister, was assassinated in a massive bomb blast. Hariri was seen as a close ally of the West and the Saudi Kingdom, and he was actually a Saudi dual-national. Syria and Iranian-backed Hezbollah were widely suspected of being responsible for the attack, and on March 8th and March 14th there were massive protests in support of and opposition to Syria’s intervention into Lebanese politics. Lebanese political parties are now divided into two major blocs, the pro-Syrian/Iranian March 8th Alliance and the pro-Saudi and pro-Western March 14th Alliance. Religion plays an important role in support for either bloc: the March 8th Alliance is dominant Shi’a regions, while the March 14th Alliance receives most Sunni votes, Christians are split. The pro-Syrian/Iranian March 8th Alliance currently controls government, to the irritation of Saudi Arabia. The Saudi Kingdom sees both Iraq and Lebanon as areas of conflict with Iran where it has lost ground recently, which has compounded its response to civil wars in Syria and Yemen.

As I have written about Syria before I will limit my description of the conflict there. The Assad regime in Syria was one of the first Arab states to support the revolutionary government in Iran and has been a consistent ally ever since. Iran’s support for the Assad regime has been associated with the sectarian nature of the Syrian government, which is dominated by followers of the Alawite community. Alawites are adherents of the Twelver sect of Shi’a Islam but also have their own unique practices. Before the start of the civil war, Sunni Arabs (the largest group in Syria) were included in many government posts, but the increasingly brutal conflict has all but eliminated their role in the government. But Iran’s support for the regime has more to do with regional politics than religion. Syria borders Israel and Lebanon, and is closely linked to Hezbollah, a group of such geopolitical importance that it is often called Iran’s aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean. For Iran, losing Damascus could mean losing an important strategic alliance. Saudi Arabia, for its part has been arming Syrian rebels under the banner of Sunni political Islam; these militias not only battle the Assad regime, but also fight the al-Nusra Front and Islamic State, who similarly draw support from the Sunni Arab community. As the Assad regime was an ally to Iran, one could argue that Saudi Arabia is looking to enhance its influence here while Iran seeks to maintain the status quo.

As I have written about Syria before I will limit my description of the conflict there. The Assad regime in Syria was one of the first Arab states to support the revolutionary government in Iran and has been a consistent ally ever since. Iran’s support for the Assad regime has been associated with the sectarian nature of the Syrian government, which is dominated by followers of the Alawite community. Alawites are adherents of the Twelver sect of Shi’a Islam but also have their own unique practices. Before the start of the civil war, Sunni Arabs (the largest group in Syria) were included in many government posts, but the increasingly brutal conflict has all but eliminated their role in the government. But Iran’s support for the regime has more to do with regional politics than religion. Syria borders Israel and Lebanon, and is closely linked to Hezbollah, a group of such geopolitical importance that it is often called Iran’s aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean. For Iran, losing Damascus could mean losing an important strategic alliance. Saudi Arabia, for its part has been arming Syrian rebels under the banner of Sunni political Islam; these militias not only battle the Assad regime, but also fight the al-Nusra Front and Islamic State, who similarly draw support from the Sunni Arab community. As the Assad regime was an ally to Iran, one could argue that Saudi Arabia is looking to enhance its influence here while Iran seeks to maintain the status quo.

(Military situation in the Syrian Civil War as of February 1, 2016. Source)

For most of its history Yemen been dogged by instability and a lack of national unity. For much of the last century it was divided between the US-backed Yemen Arab Republic in the north and the Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen in the south. After the fall of the Soviet Union the two countries were unified but conflict between the north and south soon arose. The southern rebels were put down violently by president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who consolidated power and continued to rule with an iron fist, including by in a decade-long conflict with the Shi’a Houthi rebels. The Houthis (named after their spiritual leader) are a rebel group in Yemen that draws on support from Zaidis in northern Yemen, where they are concentrated. Zaidis are fellow Shi’a Muslims but follow a different jurisprudence than the Alawites in Syria or the Twelvers in Iran, and the community has long criticized its treatment by the central government in Iran.

In 2011 president Saleh faced a popular uprising similar to those seen in Egypt and Tunisia and in short time he had fled to Saudi Arabia. His replacement, Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi faced the unenviable task of uniting the disparate regions of the country while also battling an active insurgency by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. This task became insurmountable when the Houthis united with pro-Saleh Sunni tribes in the north in a bid to overthrow the Hadi regime in 2014. In short time the capital Sana’a was overrun, forcing Hadi to dissolve parliament and flee to the southern capital Aden. The Saudi Kingdom has long accused Iran of backing the Houthis (though little has been substantiated) and perhaps because of this, it has responded very aggressively to the fall of Sana’a to the Houthis, waging an expansive military campaign in the country. In a way, Yemen acts as a good example of the security dilemma facing Saudi Arabia and Iran: just as Iran fears losing influence in Syria, Saudi Arabia fears losing influence in Yemen, both have responded to these fears with military escalations.

(Situation as of 3 February 2016: Red = Controlled by the Hadi government and the Southern Movement, Green = Controlled by Houthis, White = Controlled by Ansar al-Sharia/AQAP forces, Grey = Controlled by Islamic State. Source)

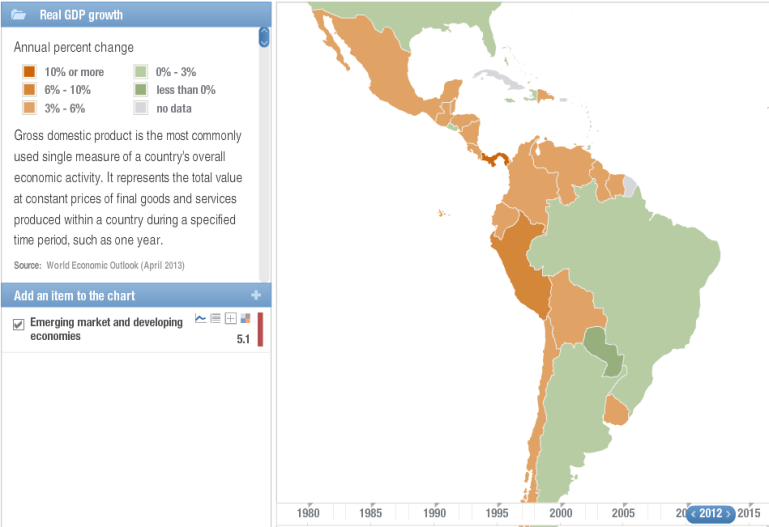

Both Yemen and Syria were republican states that were heavily criticized for their oppressive and corrupt practices; it is little surprise that they’re facing internal conflict now. One of the biggest drivers of instability in the Middle East has been the failure of revolutionary Arab Republics to deliver meaningful improvements in the lives of their citizens. Unlike the monarchies which can claim historic and religious ties to their governance, Arab Republics only ever had their own record to rely on for legitimacy. Arab Republics have by far been the biggest victims of revolution and instability since the beginning of the Arab Spring in 2011.

Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Libya and Tunisia have all seen their regimes either toppled or fighting for their life in the new Middle East. These regimes all started out as revolutionary republics that promised to transform economic and political fortunes of their citizens but failed in a variety of ways. They quickly morphed into repressive dictatorships with sprawling bureaucracies designed to suppress dissent. State terror is so common throughout the region that all Arabs share common word for Secret Police: the feared Mukhabarat. Arab Republics not only failed to create space for political expression but also failed to improve their economies. In 1960 Egypt and South Korea had similarly sized economies and populations; they aren’t even in the same category of development today. Iran and Saudi Arabia themselves have similarly repressive state structures (the Baseej in Iran and the Mabahith in the Saudi Kingdom) but their legitimacy hasn’t been as thoroughly shaken as the Arab Republics have been. The collapse of Arab Republics both as effective states and as a political model has helped to create the power vacuum we see today, where Iran and Saudi Arabia fight to enhance their influence both militarily and ideologically.

It is my opinion that neither side will be successful in defeating the other through ideology or military power. Iran’s influence outside the Shi’a community has been limited, as evidenced by its complicated relationship with the Sunni Palestinian group Hamas. But Saudi Arabia faces its own obstacles: by bankrolling Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s regime in Egypt and helping to crush of the Muslim Brotherhood there the Saudi Kingdom has alienated many mainstream Sunnis and potential allies against Iran like Qatar and Turkey. Saudi Arabia has long relied on US support, but this been strained by the recent nuclear accord with Iran and fears that the US wants to enter into closer relations with Iran. These fears aren’t entirely unfounded as the US and Iran share a strategic interest in defeating Islamic State, which Saudi Arabia is less willing to confront. Yet Iran has also alienated potential allies through its aggressive intervention in Syria and Iraq.

Unfortunately for the people of living in these areas of conflict, it seems unlikely that this rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran will end anytime soon. In Syria the conflict rages on while the Vienna peace talks have been suspended after a hopelessly fragmented opposition failed to agree on what representatives to send; meanwhile the most effective opposition groups (al-Nusra and IS) aren’t even participants. The powers that are participating in the Syrian civil war (including Saudi Arabia and Iran) seem totally willing to continue supporting belligerents there.

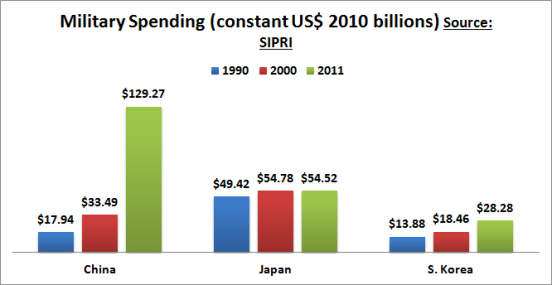

A major factor that pushes each side toward a continuation of conflict is the imbalance between perceptions of power and actual power in Saudi Arabia and Iran. Iran’s opening with the West over its nuclear program will certainly lift its economy, and it was already one of the largest economic centers in the region. It already has a longstanding history of successfully intervening in other countries in the region through the IRGC, which is as old as the Iranian revolution itself. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has a massive supply of foreign-exchange reserves and a modern (and expensive) military. And yet both of these countries view themselves as under threat by the other. It is this imbalance between perceived power and actual power that I believe will lead to a continuation in their regional conflict in the near future.