Well, it’s been a while! In my defense, I’ve moved across the world since I last wrote here, and I now have to contend with some very loud birds as I write this. But I have good reason to write now; so much has transpired since I last wrote. You’ll have to forgive me for the length of this blog post, if you read it in it’s entirety you’ll have digested over 3000 words, there’s just so much to write about. With a remarkable confluence of political transitions taking place across the globe, there seems now, even more-so than in 2012, a real opportunity that the world will look very different 12 months from now. From the reelection of Barack Obama to Xi Jinping’s ascent to top spot within the Communist Party of China, many regions appear poised for change and uncertainty. From Israel to Myanmar there has been no shortage of speculation and intrigue regarding what the future will bring. But while there have been notable transitions across the world, some regions seem to have experienced less upheaval than others… so far.

Europe

Twelve months ago the world was fixated on the volatility of the European debt crisis and what might happen if an anti-austerity party won in Greece. This did not come to fruition, and while the anti-austerity party Syriza became the official opposition, they remain far from power in Greece. With relatively mundane results in the other European elections (Czechs and Slovenes both elected remarkably boring presidents) you might wonder if Europe really belongs in a blog about political upheaval in 2013. The good news is that very soon that will change, thanks to a combination of factors in Italy’s general election on February 24th.

After resigning in 2011, few could have imagined that the scandal-ridden media mogul would return to politics, but underage prostitute scandals notwithstanding, Berlusconi will contest yet another election. He will lead the People of Freedom party against the social-democrat PD, which is leading in polls at the moment; but in an added twist he will be competing with two other unlikely figures for the job.

When Mario Monti was asked to form a technocratic government in the wake of Berlusconi’s resignation he was not expected to contest the election after his government implemented economic reforms, but on December 28th he announced he would run for Prime Minister under the “With Monti for Italy” party. While Monti’s entrance into politics may have been surprising, his background is very different from the leader of Five Star Movement. Beppe Grillo entered politics as a comedian and blogger, and has taken Italian politics by storm; at one point his party scored as high as 20% in national opinion polls, though its popularity has since waned. The Five Star Movement can be defined broadly as an anti-austerity party, though some of Grillo’s other policy prescriptions include more direct democracy and free internet. While few expect either Monti or Grillo to garner enough support for the top spot, their impact on the election could be vast.

Public polling has consistently placed the center-left Democratic Party (PD) in first place, but the latest polls hinted at the possibility of a hung parliament in the Senate, where seats are allocated on a regional basis. This would force Pier Barsani (leader of the PD) to form a coalition, either with Mario Monti or even Beppe Grillo, though this is unlikely. You might wonder why the election in Italy is getting so much attention when so many different political transitions have taken place. Italy sits in a unique place within the EU: while it has come under scrutiny for its large debt (only the US and Japan have more) and its sluggish economy (only Zimbabwe and Haiti grew more slowly from 2000 to 2010) it also commands the largest share of the Eurozone economy outside of Germany and France. It also holds the distinct role of being the largest Eurozone member that is currently undergoing harsh austerity, which is being administered by an unelected, technocratic government. France has already replaced the center-right government of Nicolas Sarkozy with Socialist Francois Hollande, in part because of his promise to transition Eurozone policy away from austerity. If a center-left government emerges in Italy, it might just be enough to move EU policymakers away from austerity, or at least away from its current manifestation. Lastly, Italy’s election matters because it precedes an election in Germany in September, where Angela Merkel’s center-right coalition has faced recent difficulties.

Middle East/North Africa

When revolutions swept the Arab world in 2011, it seemed like the greatest emotion expressed in the crowds was relief and optimism; since then, ambiguity has shrouded interpretations of events.

This picture was taken in Tunisia on Feb. 6th of this year (source: Reuters/Anis Mili). The killing of left-wing opposition leader Chokri Belaid has sparked the largest demonstrations in Tunisia since the government of Ben Ali was overthrown two years ago. The Islamist-dominated government has dissolved parliament in response to this, and is calling for fresh elections in the wake of the unrest. Elections that took place in Tunisia and in Egypt after their respective revolutions saw Islamist parties win the largest share of the vote. While the outcome of the election was not disputed (unlike Iran in 2009) within those countries or by observers, the conduct of the resultant governments has been very critical. Mohamed Morsi, the president of Egypt and member of the Muslim Brotherhood has seen his first term riddled with controversy ranging from his handling of the drafting of a new constitution, to recent violence between police and demonstrators. Instead of focusing on these internal debates taking place in Egypt and other MENA countries, I’d like to talk about the regional implications of recent political transitions.

Two countries that dominate media coverage of the Middle East and I think warrant special attention for their regional impact are Israel and Iran. Both countries have an awkward (to put it nicely) relationship with many of their neighbors, and both essentially exist on the opposite sides of a diplomatic arrangement with the US. Iran has counted on support from Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Assad regime in Syria, and Shi’a leaders in Iraq, surprisingly.

I mention Iraq as a surprise because this wasn’t always the case; before the US invasion in 2003 Saddam-governed Iraq was actually a fierce opponent of the Islamic Republic in Iran. From 1980-88 they fought a protracted war that cost half a million lives, both Saddam Hussein and the Ayatollah sought to overthrow the regime in the other country. After the first Gulf War, the US engaged in a policy of “dual containment” that attempted to limit the influence of both regimes simultaneously. While this strategy was broadly viewed as “stupid” and had limited success containing either regime, the effects of the US occupation in 2003 had a more dramatic impact on regional influence. Nouri al-Maliki, the current prime minister of Iraq, is Shi’a Muslim (the main religion of Iran) and has close ties to the Islamic Republic in Iran, he actually lived there in exile for most of the 1980s. With the elections in 2005, Iraq has become one of Iran’s closest regional allies and has even helped sustain the Assad regime in Syria, another close ally to Iran.

Iran’s relationship with the other Arab regimes has been far less fruitful. Egypt and Iran have had icy relations since the revolution in 1979. Most notably, the Islamic Republic named a street in honor of the man (Khalid Islambouli) who assassinated Egyptian president Anwar Sadat. A precursor to this diplomatic freeze was Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel in 1978, as Iran viewed (and continues to view) Israel as its greatest enemy. The ascent of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt has helped improve relations, but the two countries remain far from rapprochement thus far. Perhaps the biggest illustration of these complicated new relations came with Ahmadinejad’s visit to Cairo on Feb 5th.

While Ahmadinejad was given a warm reception by President Morsi, he was grilled by other political and religious figures, most notably for Iran’s continued support of the Assad regime in Syria. In many ways the paths of these two countries were destined to be complicated, by both history and their sectarian importance. One of the tenser moments during the visit occurred when the leader of al-Ahzar (one of the most respected Sunni institutions in the world) grilled Ahmadinejad over everything from Syria to the belittlement of Islam’s first caliphate. Egypt is the most populous Arab country, and in a way it represents the broader Sunni-Arab aspirations in the region. Iran has a similar population, and it’s religious institutions in Qom are viewed with comparable regard to al-Ahzar for Shi’a Muslims across the world. This theological rift turns political when it comes to Syria, where the two countries continue to be at odds over the future of the Assad regime. I don’t want to oversimplify matters excessively: the Muslim Brotherhood’s relations with some Sunni regimes in the Gulf have been frosty at times.

Under this backdrop, the Israelis voted on Jan. 22nd, with most expecting Benjamin Netanyahu’s new Likud-Beiteinu bloc would sweep to victory, however things were not that simple.

(source: Ilia Yefimovich/Getty Images)

(source: Ilia Yefimovich/Getty Images)

The man pictured above is Yair Lapid, a TV presenter-turned politician who now leads the second largest party in Israel, Yesh-Atid (translated: There is a Future). While Yesh Atid was expected to win about 10 seats, he nearly doubled this total with 19. Most of Mr Lapid’s platform was very centrist, with broadly popular ideas like reducing corruption and reforming education getting mention. More controversially he also proposed ending the exemption on Haredi (ultra-Orthodox Jews) from military service and negotiating with the Palestinians with the goal of creating a two-state solution. This latter declaration is significant because even after tacitly accepting a two-state solution, Netanyahu has done very little to indicate that he takes the idea seriously. Even after reaffirming his commitment to two-state solution, he said that the Palestinian Authority needed to drop any preconditions on talks, even as his government moves ahead with the controversial E1 settlement plan.

Lapid has also differentiated himself from Netanyahu on Iran, saying the Likud leader has been too confrontational towards the Obama administration regarding Iran, saying “[Netanyahu] thinks he can drag America to do what it doesn’t want to do. He is leading Israel to war too soon, before it’s necessary.” While it is less clear what meaningful differences they have w-r-t Syria, the biggest question right now is what government, if any, can emerge from this fragmented election:

(Source: BBC) Coalition talks are expected to be very acrimonious as they have to first be led by Netanyahu (who won the most seats) who has been weakened by this electoral result. His list lost 11 seats and he is coming under scrutiny for his role in a variety of troubling and quite funny scandals. Whatever the outcome, the region faces a range of crises, from Syria’s civil war to the economic malaise that affects so many countries in the Middle East; now, more than ever, is a time for effective leadership in the region.

Asia

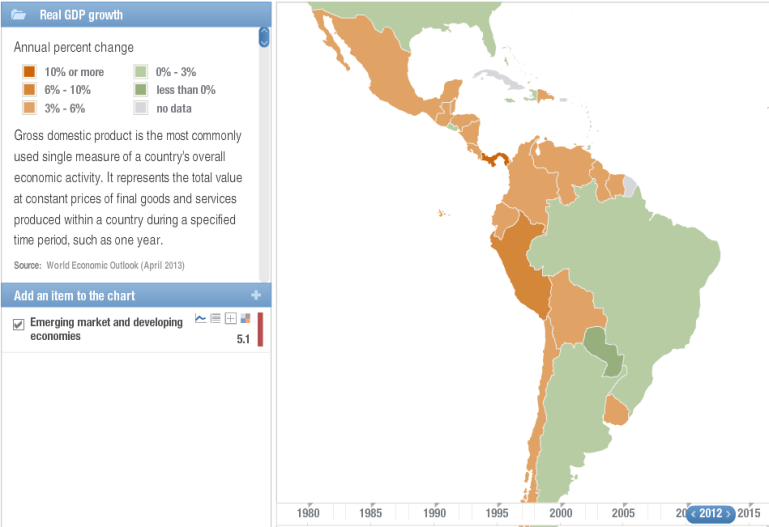

Perhaps more than any political transitions that have taken place this year (including the US election) changing of guard in China, Japan, and South Korea. Xi Jinping, Shinzo Abe, Park Geun-hye have all been elected to lead their countries in a time when East Asia represents an increasingly important economic area:

(source)

(source)

Unfortunately this increased economic importance is being supplemented with increasing hostility between the respective governments, with the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute receiving a great deal of media coverage. While the dispute has been simmering for over a century, things came to a head when in September Japan decided to nationalize part of the island chain, setting off a diplomatic row with China that has caused alarm across the globe. While Japan’s purchase of the disputed islands from a private owner may seem like an obviously provocative act (it certainly was by China), the action was actually intended, however clumsily, to deescalate tensions. This is because the bellicose mayor of Tokyo, Shintaro Ishihara had stated his intention to buy the islands; Japan’s government feared he would use his ownership to provoke China publicly. Things have escalated quickly since then, with anti-Japans protests and boycotts enveloping China. Perhaps most disconcerting has been an allegation by Japan that China had targeted one of its vessels near the islands with it’s fire-control radar.

(Source: The Guardian)

(Source: The Guardian)

History has played an increasingly important and often detrimental role in island disputes in East Asia; the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute is only the most recent example. Last summer a series of symbolic gestures were taken by the South Korean government to underscore its control of the Dokdo/Takeshima Islands, whose control is disputed with Japan. What came next surprised many when South Korean President Lee Myung-bak said that were emperor of Japan to visit Korea he would demand an apology for Japan’s crimes in WWII. Lee is no longer in office, his party instead nominated Park Geun-hye to run in the 2012 Presidential election, which she won narrowly. She campaigned on a platform of economic liberalization but at deftly supported reforming the state’s relationship with the Chaeobol (powerful family-owned businesses). Perhaps more than her policies, she has been scrutinized for her own history: she is the daughter of the late dictator Park Chung-hee, a controversial figure in South Korea. She, like her predecessor has demanded that Japan apologize for its crimes in WWII, though her own nationalism is now being matched by a flamboyant counterpart in Japan.

Shinzo Abe was elected Prime Minister of Japan on a platform of expansionary economic policies (which have many left-wing champions) and a nationalist foreign policy. In October Abe visited the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, where some Class-A war criminals are enshrined; in the past he has suggested Japan should review its apology for using comfort women in WWII. Though he shelved this latter plan, his other, less symbolic proposal could signal bigger, more worrying development for neighboring countries. Shinzo Abe has suggested his government will review its interpretation of the Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution which under it’s current interpretation prohibits an act of war by the state. This has been justified as enabling Japan to engage in “global security operations” as well as allowing its military to engage in joint military operations with its allies, such as a strike on North Korea. It seems clear that while this might be accepted in Seoul and Washington, it will raise eyebrows in Japan’s biggest neighbor.

As alluded to earlier, the recent hostility between Japan and China has received most of the coverage in this region recently. In many ways the anxiety over the confrontation between Japan and China comes from the the transformation in roles the two countries have had economically:

Only fifteen years ago Japan laid claim to the largest economy in East Asia and despite it’s economic headwinds (the 90s were considered Japan’s “lost decade”) few anticipated the quickness with which China would overtake it. For perspective, in 1990 when Japan was considered the chief economic rival of the US, its GDP was $3.018 trillion compared to China’s $355 billion it’s growth rate was for that year was 5.57% compared with China’s 3.8%. Japan’s economic performance was so strong that it captured the fear and imagination of the American public, with popular books and films depicting a Japanese takeover of American businesses. But after 1990 events took a dramatic turn in East Asia; China (and to a lesser extent S. Korea) has overtaken Japan in GDP every year since:

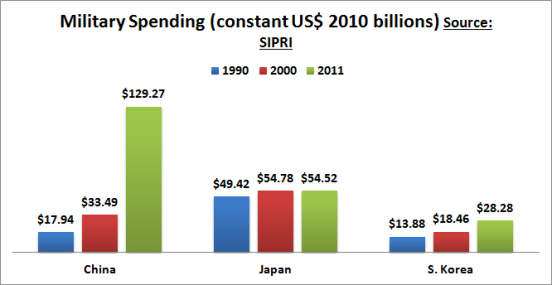

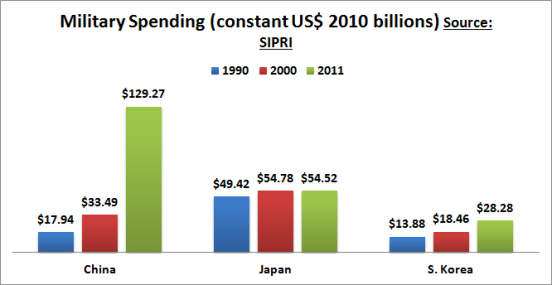

Presiding over this record-breaking growth has been a series of modernizing figures in the Communist Party of China starting with President Jiang Zemin and Premier Zhu Rongji. Their role in directing China’s State Capitalist model cannot be understated, with their successors Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao largely following the same path. With the exception of a brief period of slower growth in 2012 the Chinese economy has looked unstoppable, but this has not stymied the internal debate about the future of China’s economy. Lost in the controversy over Bo Xilai’s role in the murder of Neil Heywood was a vigorous debate about the direction of China’s economy. Bo’s governance of the Chongqing Province was seen as a good model by observers in China and abroad. The model was characterized by its high levels of foreign investment as well as large state-sponsored projects, and succeeded in producing levels of growth that beat the national average while he was premier there. Due to his dramatic downfall, his ideas will have to be debated by Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang, who will formally be declared President and Premier of China March this year. They will preside over not only the largest economy in East Asia, but also the largest military as well:

(you should really get this if you want to know more about global military spending) The Senkaku/Diaoyu Island dispute comes at a time of unprecedented disparity in military spending between the two countries, unfortunately it is being coupled with unprecedented nationalism on both sides. What is particularly worrying is how lightly both sides seem to be taking the risks of escalation, especially considering the US declaring itself treaty-bound to defend Japan’s control over the Senkakus. One can only hope that the negative externalities that are at stake will compel both sides to deescalate the dispute. This is important not only because of the risks of conflict, but because of the urgent need for cooperation among the three East Asian powers. North Korea’s nuclear test just last week and it’s threat to conduct more is perhaps the best current example of this need. The world’s most important economic region needs pragmatic leadership now more than ever, it is truly disappointing to see nationalism cloud what was otherwise considered such a promising future for the region.

In all of the examples of political transition I have mentioned here there seem to be forces that both promote the status quo as well as forces agitating for change. In this blog I focused on the forces agitating for change, in part because I find this more compelling. You might have noticed that there were many notable omissions from this blog, I certainly do not wish to underestimate the importance of these political transitions. From Myanmar’s democratic reforms to Enrique Peña Nieto returning Mexico’s presidency to the PRI are just as important to the future as Japan’s recent elections. I will not, however, apologize for omitting the recent election in the United States. Due to my own interest/connection to US politics, I followed the election very closely. If you did not and would enjoy some analysis, I suggest you look somewhere else for relevant coverage: here are a few of my personal favorites.