I have been conflicted over writing a followup post to my original blog written in 2012 (eek!). Many aspects of the conflict have changed since then and they have been mostly been for the worse. In addition to these negative updates, events have unfolded at break-neck pace: not long ago ISIS (now Islamic State) operated in a small section of eastern Syria and western Iraq. The fast-changing and often grim news emanating from the region put me off of writing more about it. The barbaric execution of Western journalists and aid workers and other recent events in Iraq and Syria have compelled me to write an updated blog about the situation there. My goal in this blog is to explain some of the historical causes for the recent outbreak of violence, but also to try to elucidate the broader ideological and geopolitical conflicts that are currently taking place throughout the region. Why are some parts of Iraq and Syria aligning with IS while others resist?

For many it will not be news that the sectarian divide among Sunni and Shia muslims predates the existing conflict by a long mark. The way the media has portrayed this conflict as both ancient and interminable (just as the Arab-Israeli conflict is portrayed) is too simplistic and ignores the relatively modern origins of the regional conflict taking place now. The schism between Shia and Sunni Islam is rooted in a disagreement over who should govern muslim world after the death of Muhammad, and thus the schism in Islam is as old as the religion itself. But while the two communities had a violent confrontation in their early history (more here) there was also a long period of coexistence and a status as co-religionists. Perhaps the biggest historical event to change this status was the conversion of the Safavid Dynasty (1501 to 1722) to Shia Islam. This conversion turned a theological dispute into a geopolitical conflict, as the Safavid empire fought a series of wars with Sunni empires such as the Ottomans and the Mughals. Even after the dissolution of these empires and the formation of modern nation states, their legacy remains:

(source)

(source)

Beyond converting what is now Iran to Shia Islam, the Safavid empire also (forcibly) converted the regions that now make up Azerbaijan and Central/Southern Iraq, which is reflected in their modern religious demographics. While the Safavid empire was not solely responsible for the spread of Shia Islam throughout the Middle East, it changed the religion’s relationship with both the Safavid empire and the subsequent Iranian nation. Unlike Sunni Islam, which has had many capitals over time (Istanbul, Cairo, Damascus, et al) Shia Islam’s theological and cultural centers are mainly in Iran. This has meant that for many Shia muslims, religious guidance and doctrine has come from Iran; whether in the form of Iranian-educated Imams (Musa al-Sadr, Ali al-Sistani, for example), or through edicts (Fatwas) issued from Qom, Iran itself.

When the Iranian revolution took place in 1979 the state was transformed from a monarchy into an Islamic Republic, under the organizing principle of Vilayat-e Faqih or “Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist.” This theory, which was created by Ayatollah Khomeini prior to the revolution, posits that one Shia muslim jurist (or Supreme Leader) should have guardianship over all issues for which Prophet of Islam and Shi’a Imam have responsibility, including governance of a country. Iran’s transformation into an Islamic Republic as well as its importance to Shia muslims proved destabilizing in the region.

When the Ayatollah called for a similar Islamic Revolution in Iraq he was met with hostility from Saddam’s Ba’athist regime in Baghdad. In September 1980 Saddam invaded Iran under the auspices of incorporating the Khuzestan province (with a large Arab population) into Iraq and eventually overthrowing the Islamic Republic in Iran. While the Iraqi regime did not have an explicitly Sunni organizing principle (the Ba’ath party was secular and Arab-nationalist) it was dominated by Sunni Arabs. As the war continued Saddam was forced to withdraw from Iranian territory; in 1982 the revolutionary leaders in Iran invaded Iraq with the hope of overthrowing the Ba’athist regime and introducing a Shia Islamic Republic there. After eight years neither side was successful and the status quo was reintroduced after a cease fire in 1988. This war, which lasted eight years, served as an introduction for the new geopolitical context that sectarian divisions would exist under. Iraq’s Shia-dominated government has many links to Iran, and some of the Shia militias fighting Islamic State are funded/directed by Iran.

Iran’s overt support for the Shia community in Iraq would continue long after the war but did not stop there. Historically, the Shia community in Lebanon was one of the poorest and worst represented of the religious communities there. Despite having a larger population than either the Christians or the Sunnis, they received the least prominent role (Speaker of the House of Representatives) under the original confessional model. A major effort was made by Musa al-Sadr, an Iranian-trained Shia Imam empower the Shia community of Lebanon, forming the Amal movement before his mysterious disappearance in 1978. As the Lebanese civil war entered a third bloody stage (1982-1990) Iran became involved when it sent 1500 Iranian Revolutionary Guards paramilitary into southern Lebanon to support Shia militias fighting there. These militias would eventually form Hezbollah, a party-cum-militia which would be blamed for a series of attacks against Israel and the US during the conflict. Hezbollah was the only group not to disarm after the Taif Agreement that ended the civil war and would continue to receive military and financial support from Iran.

In Syria, Iran’s role has been both overt and multifaceted. The Iranians have had a long alliance with the Alawite-led government of Bashar al-Assad ever since the Iranian Revolution in 1979. This relationship has a religious component as the Alawite faith is a branch of the Twelver school of Shia Islam (practiced in Iran) but with syncretistic elements. Support for the Assad regime has included direct military assistance, arming Shia and Alawite militias, and sending Hezbollah (the Shia militia based in Lebanon) to fight on behalf of the Assad regime.

(picture taken by me in Damascus, Syria in 2010. From left to right: Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Bashar Assad, Hassan Nasrallah)

When looking at Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon the role of religion and ideology is undeniable: Iranian trained clerics like Ali al-Sistani and Hassan Nasrallah, who subscribe to the state ideology of Iran (Vilayat-e Faqih) lead Shia communities that are more supportive of Iran than their Sunni compatriots. But behind this broad trend of political views coinciding with sectarian ones there are differences. Iran’s anti-Western geopolitical orientation and its support for anti-Western governments/groups such as Bashar Assad in Syria or Hezbollah in Lebanon is sometimes attributed to the view of all Shia communities, however unfairly. This was especially troublesome during the 2011 Bahrain protests, where the Shia majority rose up against the Sunni monarchy, only to have the protesters unfairly linked to Iranian subterfuge. Even after the 2003 US led invasion of Iraq, Shia Arabs have a more favorable view of the US than Sunni Arabs (Kurds in Iraq have the most favorable view of the US):

(source: Zogby, poll conducted in 2011)

This survey is quite instructive in underlining the complex relationship between geopolitics and religion in the Middle East. Shia Arabs view Iran more positively than either Sunni Arabs or (mostly Sunni) Kurds, while Sunni Arabs view Saudi Arabia (KSA on the survey) more favorably than Kurds or Shia Arabs. What this survey is also helpful in illuminating is the efforts that have been made by various regional actors to engage with the various communities of Iraq. It is no coincidence that Turkey and Saudi Arabia have both worked hard to establish relations with the Sunni Arab leaders in Iraq, though Turkey has also made inroads with the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) and some Shia leaders.

Saudi funding for Sunni militias in Syria and its support for Sunni Arabs in Iraq also has considerable history predating the rise of Islamic State. Saudi Arabian support for Sunni militia and its opposition to Shia movements has deep roots, going back to the the very founding of the modern Saudi Kingdom after the fall of the Ottoman empire. Many muslims in Saudi Arabia are followers of the the Wahhabi/Salafist movement, an ultra-conservative sect of Sunni Islam that posits that Shia Islam is not a legitimate form of Islamic faith. Prominent clerics in the Kingdom have preached violence against Shia muslims in Iraq and a great deal of money flowing to hardline Sunni militants (including Islamic State) has come from private donations from Saudi Arabia as well as other parts of the Gulf.

Turkey, itself a large, majority-Sunni nation with a democratic (though increasingly authoritarian) moderate Islamist government lead by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has tried to gain influence among Sunnis in the region by touting its own model of political Islam. A notable difference between Turkish and Saudi engagement in the region has been the relatively good relations Turkey has had with Iran while Erdoğan has been in power. Saudi-Iranian relations, on the other hand have been poor for a very long time, with many viewing the two states as rivals in the region. Turkey often finds itself, paradoxically, in a rivalry with the Saudi Kingdom over influence with Sunni muslims in the region and beyond. This is a good example of a contradiction I’ve mentioned before: because there is no dominant cultural/theological center for Sunni Islam, there is no one state or even one ideology which successfully advocates on behalf of Sunnis as effectively as Iran does for Shia muslims.

Indeed, the two major ideologies within Sunni Political Islam today that both promote an Islamic role in government, though they differ widely in their interpretation of this role. Followers of the Muslim Brotherhood, a movement founded in Egypt, advocate for an Islam-inspired government that uses Islamic Law (Sharia) as either the partial or sole basis of their constitution, but wish to create a modern state with a modern economy. Salafists, on the other hand, wish to reintroduce an Islamic Caliphate and create a society modeled on the original Islamic empire, sometimes called the Islamic Golden Age. Generally, Salafists view Shia Islam and Iran critically, and have been vocal in their opposition to the Iranian state. Christians and other non-muslim minorities have also come under fire from Salafist groups at times. While there are non-violent Salafist movements like the al-Nour party in Egypt, there are violent jihadist movements like Islamic State and al-Qaeda who all share the same political vision, if not the same tactics to achieve it. While these militant groups have received some support from private donors, they have limited support by states in the region. In truth, the Salafist’s political vision threatens all contemporary majority-Sunni states, perhaps more so than to majority-Shia ones. I believe that this is why the coalition to fight Islamic State includes many Sunni Arab states.

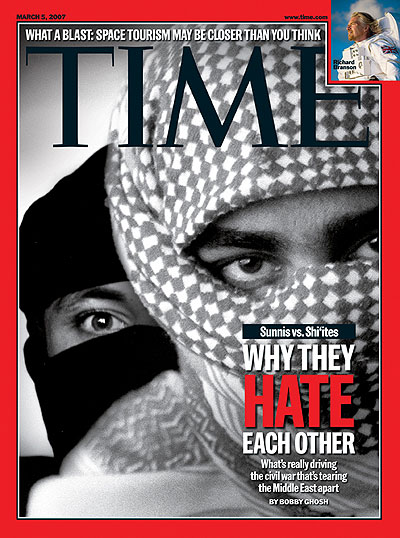

This headline from 2007 underscores just about everything that has been wrong with the coverage of the sectarian divide in Islam. Media in the West has repeatedly covered this conflict as one of “ancient hatred” that has been smouldering since the eighth century. What is missing here is an explanation of how the Sunni-Shia schism was transformed from a theological rivalry to a geopolitical one; key events like the the Safavid conversion to Shia Islam in 1501 and the 1979 Iranian Revolution helped produce this outcome. While the two communities certainly foster some distrust of the other, historically relations have been nuanced, particularly in countries with large mixed communities. Much of the fears that Sunnis and Shia have come from a very real place. Shia muslims have been historically marginalized in much of the Middle East and beyond, only very recently have they been politically empowered in places like Iraq and Lebanon. Many Shia muslims fear annihilation by well financed Salafist groups like Islamic State and al Qaeda, a fear not unreasonable given recent events. Sunnis in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere fear a future of domination and reprisals by Iranian-backed governments that will have little interest in including Sunnis in the political process. Again, these fears are not unfounded given recent events. Unfortunately, it is hard to see an outcome that calms these anxieties in the near future. In the West we can choose to leave this conflict, ignore its impact, but for the inhabitants of the Middle East, this melding of geopolitical and sectarian considerations will persist. I fear that the Iraqi Sunni Arabs will pay a very high price for their support for Islamic State.

We like to think that this mixture of religion and politics is foreign to us, but in reality there are modern examples of Christian sectarian hysteria in West. Imagine if there were very powerful, highly militarized states advocating for a politicized version of Catholicism and Protestantism in the West; it isn’t hard to imagine that our own perceptions of faith and politics would be different if this were the case.

Update: Here are some important links for up to date information on Iraq and Syria.