Ethnic and religious minorities in the Arab world have long fascinated me. The Middle East is home to a variety of ethnic and religious communities with ancient origins; in the village Maaloula in Syria the last remaining speakers of Western Aramaic (the language spoken by Jesus) reside. While the community that lives in Maaloula is tiny (2,000 people live there) the region contains many larger groups. This can complicate nation-building and has led to some hilariously complicated political alliances. When I visited the region in 2010, I was particularly amazed at the concentration of groups into enclaves.

I took this picture in Gemmayze district in Beirut. The circular sticker with a tree in the center is actually the symbol of the Lebanese Forces, a militia-come-political party that represents Maronite Christians in Lebanon. A short taxi ride to the south of Beirut, near the Shatila refugee camp you find very different political signs along with different demographics:

In the 2006 war with Israel this area was bombed; most of the people here belong to Shi’a Islam and support either Hezbollah or Amal, whose late founder Musa al-Sadr is pictured here. Lebanon is not the only country with a unique mixture of communities, as the recent hotspots of the Arab Spring demonstrate: minorities play a big role in the outcome of the Arab Spring.

I was thrilled to add Syria to my trip after I arrived in Beirut. Many things distinguish Syria from the other countries in the region; the country’s diversity is just one of them. Syria has been in three declared wars with Israel (1948, 1967, 1973) and numerous other conflicts indirectly. Since 1971 the country has been ruled by the Assad family, first under Hafez al-Assad and currently under Bashar al-Assad. Both Bashar and his father belong to the Alawite sect: a branch of the twelver-school of Shi’a Islam.

Before going deeper into the details of this faith I would like to explain the connection the Alawites have with the Assad regime. At the time of independence from France (1946) the Alawites were marginally represented in Syrian society; most of them lived in the mountainous area east of Syria’s coast, near Latakia. Young Alawi men began to join the military in large numbers, particularly the Air Force after Syria’s unsuccessful war with Israel in 1948. One of those men was Hafez al-Assad, who would become commander of the Syrian Air Force after a coup by the Ba’athist party in 1963. In 1966 the Ba’athist Party had an internal coup and by 1971 Hafez Assad would become the leader of an authoritarian Syrian state. The role of Syrian Alawites has been transformed since then.

In many ways the Alawi people of Syria face a similar dynamic that the Sunni Arabs of Iraq under Saddam Hussein; both groups received benefits from the state via association. Syria’s economy, like many Arab countries, is dominated by the state; about 30% of the total workforce in Syria works in the public sector. Alawites frequently direct important businesses, from private cellular companies to the real estate firms. Sadly, the darker side of this sectarian connection has been illuminated by the recent uprising in Syria: the state’s feared Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-Jawiyya (Mukhabarat for short) is controlled by the Air Force, and is currently directed by Jamil Hassan, an Alawite. The Syrian military has also increasingly relied on its 4th armored division to carry out attacks on rebels. This division is commanded by Bashar’s younger brother Maher al-Assad and is almost entirely comprised of Alawi soldiers. While the state controls this division directly, many of the gruesome atrocities recently carried out were done by militias mostly drawn from Alawite population called the Shabiha (ghost), ostensibly with support from the state.

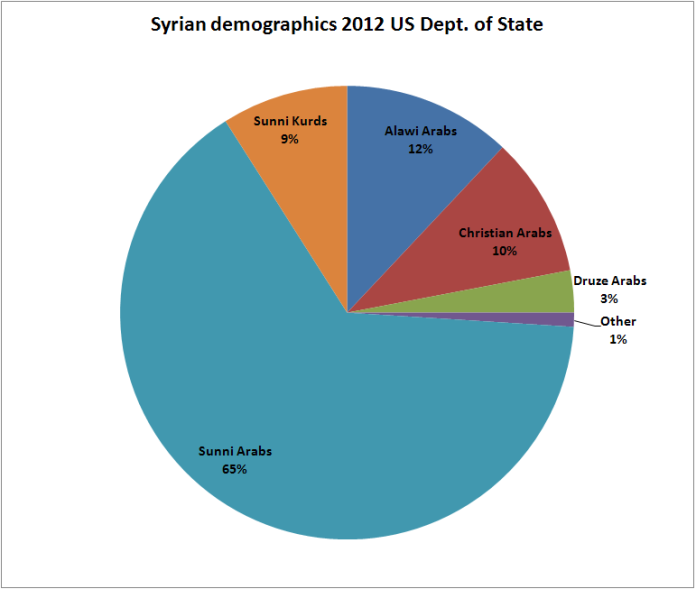

It isn’t my intention to portray the Alawites as an evil sect, or to conflate the actions of the regime with the larger community. With that said, Alawites face a future that is complicated by demographics and a unique relationship with the regime in Syria; they are hardly alone:

(note: I used statistics from the US Dept. of State in part because exact percentages for each community are often disputed by different sources while the DoS estimates are at least internally consistent)

The truth is, more than a third of Syria’s population faces an uncertain future that could be reshaped by democracy; a fact not lost on the regime. I hold the not-uncommon opinion that Assad uses the threat of sectarian conflict to raise the stakes for minority communities in Syria. I think the regime hired Alawites to carry out the massacre in Houla with the expectation that it would provoke a sectarian response by Sunni Arabs. Assad might have gotten his wish at the start of the month when footage was released of Syrian rebels executing four prisoners, allegedly members of the Shabiha based in Aleppo. But the people killed in the video were not from the Alawi sect, they reported to be Sunni Arabs from the Al-Berri clan. Whether or not the opposition is currently engaged in sectarian conflict, there are deep issues about the fate of the Alawi population in Syria once the regime collapses. Some distrust of the sect seems inevitable: the Alawi connection to the Assad regime is complicated by the secretive nature of the group, which keeps certain aspects of the faith secret.

While the Alawi have a connection to the regime poses the primary challenge to the group’s future in Syria, the Druze there face a mainly religious one. While the Alawi have a secretive past, the sect underwent a so-called “Sunnification” under Hafez Assad; this helped bring the Alawi into the mainstream and settle tensions between the Sunni majority and the small sect. The same did not happen for the Druze, whose faith is still considered by most Muslims to be a separate religion from Islam, many Muslim scholars go so far as to call it a cult. Even more so than the Alawi, the Druze keep large portions of the faith a secret and it is alleged that male believers are forbidden from learning certain principles of the faith until they are 40 years old.

In addition to the doctrinal differences that separate Syria’s Druze (about 3% of the population) there is a history of regionalism, and even brief autonomy for them during the French Mandate of Syria:

As pictured, the historic center of the Syrian Druze community has been near the mountain Jabal al-Druze. Most of this resides in the modern governate of as-Suwayda, which retains a Druze majority. While many Druze reside in this area, they can also be found in Syria’s major urban centers, Aleppo and Damascus. Despite the history of autonomy in Jabal al-Druze, Druze in Syria and in neighboring countries are known for their loyalty to the nations they live in. While the Druze of Syria have tried to avoid taking sides in the recent conflict, recent violence has drawn them in at times.

While they remain silent, the Druze living in Lebanon to the west and in Israel to the southwest have become vocal and divided over the revolution. The influential leader of Lebanon’s Druze community, Walid Jamblatt, has endorsed the opposition and asked foreign powers to help overthrow Assad. Meanwhile the Druze living in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights have become divided, with many youth siding with the opposition. It should be noted that there are about 100,000 Druze living in de-jure Israel who are integrated into Israeli society, holding political posts and serving in the military. Eventually I think the Druze community in Syria will support the opposition, but not until a more clear shift in the balance of power emerges.

If the Syrian Druze face a future partially dictated by the actions of their community abroad, the Kurds of Syria face a future dominated by it. The Kurdish people are dispersed across the region, millions live in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Broader Kurdish relations with the governments of the area have played into local politics in Syria. In 1998 Turkey nearly went to war with Syria (then under Hafez Assad) over Assad’s alleged support for the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) which was accused of terrorist acts in Turkey. Hafez Assad reversed his support for the PKK and forced its leader Abdullah Ocalan to leave Syria; relations with Turkey improved soon after.

The biggest and best armed Kurdish group in Syria, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) has recently taken control of government institutions and set up road blocks in parts of Syria’s northeast. The PYD has connections to the PKK and some have speculated that Assad is allowing the PYD to take control of the northeast in exchange for not joining the opposition. This action been condemned by some Turkish lobbyists, who see it as an opportunity for renewed violence in Turkey’s southwest. In addition to Turkey holding a position on the Kurds of Syria, Iraq’s Kurdish leaders have also become involved. The leader of Iraq’s Kurdish region, Masoud Barzani, recently got Syria’s two biggest Kurdish organizations the PYD and the Kurdish National Council to share power. This has in turn inflamed tensions between Iraq’s central government and the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG), as there was a brief standoff between soldiers in the Iraqi Army and the KRG’s Peshmerga near the border separating Iraq and northeastern Syria. While the Syria the Kurds might not be united behind either the regime or the opposition they remain united in their demand for autonomy: by now the opposition realizes that autonomy, in some form, will be the price for Kurdish support.

The article that inspired me to write this blog (from the WSJ titled: Can Syria’s Christians Survive?) focuses on the final group I want to discuss. Christians have lived in Syria since the advent of the faith, the apostle Paul famously made his conversion there and the community of Christians has stayed there ever since.

(me at the site of Paul’s baptism in Damascus)

The largest Christian denominations in Syria are Greek (Eastern) Orthodox, Eastern Catholic, Melkite Greek Catholic, and the Oriental Syriac Orthodox Church. While different sources dispute the size of the Christian community in Syria, few sources put them under 10% of the total population. Syria has experienced a region-wide phenomenon of large-scale Christian emigration over the past 30 years. The secular orientation of Hafez and Bashar Assad’s regimes has been popular with many of the Christians in Syria, this has led to tensions with the Sunni majority in places of fighting. In al-Qusayr (a town south of Homs) Christians took up arms and manned regime checkpoints. This provoked a violent response and the town was Christians suspected of supporting the regime were allegedly executed, with thousands later fleeing the city. With this painting a bleak picture for the future of Syria’s Christians, there are Christian leaders within the opposition. George Sabra is a Christian in the leadership of the Free Syrian Army, he argues that the regime is an ally to no faith and that the Free Syrian Army has had Christians in its ranks since the beginning. But even he admits that most Christians are afraid of the future and choose to stay out of the conflict as a result.

The fear of long-term communal violence has led some academics suggest partitioning Syria along sectarian and ethnic lines, but this solution is riddled with flaws in my opinion. Syria is a nation dominated by the two cities Damascus and Aleppo; over a quarter of all Syrians live in the metropolitan areas of these cities and most minorities have large communities there. The two cities might contain more Kurds than the north and northeastern sections of the country, where PYD and KNC fighters have been most active. The countries Druze might be concentrated near Jabal al-Druze but many reside in the two main cities. And while the Alawi have a heavy presence in the northwestern part of the country, their large communities in Aleppo and Damascus would be separated by hundreds of miles from any Alawite State. Finally, the country’s Christians are mostly concentrated in the two cities, but also have communities west of Homs mountains (in Wadi al-Nasara). Despite being 10% of Syria’s overall population, there appears to be no partition of the state that could protect them.

(from the WSJ article)

Some have responded that the sectarian tensions within Syria are so insurmountable that we should just give up and support the regime; again I see many problems with this outlook. It’s true that Christians have complained about the rebels and some refugees have gone on record saying:

The nightmare for Christians is when the revolution took an Islamist face, it is not the moderate Islam we know in Syria. We are talking about a kind of aggressive and impulsive Islam.”

This sentiment underscores legitimate grievances from the Christian minority, but it makes little sense to deduce from this statement that the murderous regime of Assad needs to be supported. The regime is responsible for the majority of the over 20,000 dead in Syria so far. The fighting has created a humanitarian crisis and given the UN and aid agencies a herculean task as more than 200,000 refugees pour into neighboring countries, according to the UN. It seems unlikely at this point that the regime could ever survive in its current state, regardless of outside influence. While Bashar’s father was able to quell an Islamist uprising in Hama in 1982 with similar brutality (killing 20,000 in the process) the world has changed since then. The Cold War has ended and despite Russia’s opposition to any direct action by the UN Security Council there is already evidence of material support for the rebels pouring into the country.

The region’s march toward democracy does not need to come at the expense of its religious and ethnic minorities, democracy and pluralistic societies can coexist. We should not feel like we’re faced with a choice between the autocratic oppression of the past and a new populist oppression of minorities. For democracy to thrive in the Arab world, there needs to be a change in attitudes towards minorities and towards the state itself. The violent cycle of authoritarian regimes being replaced with new ones that use violence to avenge the past has to stop. The process of finding truth and reconciliation as it has taken place in Latin America offers some guidance to this end. Until then, the alienation of minorities in the Arab world will only serve to create more enemies and continue the tragic trend of emigration by minorities.